Snowpack Summary for Friday, January 11, 2019 5:54 PM 10" this week with significant wind transport; more snow in the forecast.

This summary expired Jan. 13, 2019 5:54 PM

Flagstaff, Arizona - Backcountry of The San Francisco Peaks and Kachina Peaks Wilderness

Observers reported localized, reactive wind slabs near and above treeline in the Inner Basin, as well as cracking and whumpfing below treeline. This indicates the new load of dense snow combined with the weight of a skier is triggering the persistent facet layers sandwiched in the snowpack. Consider the consequences of an avalanche on the slope you are evaluating: size, runout, and destructive potential of a release.

Human triggered avalanches are possible, and likely on slopes with recent wind transport. Note that weak layer failure is also occurring on low angle terrain and below treeline, thus evaluating run out zones and terrain traps are advised.

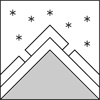

Snowpack depth has increased to a depth of 70 to 100 cm on shaded and wind loaded aspects at and above treeline. Snow profiles and stability tests from west and north aspects above treeline indicate poor structure, moderate strength, and increasing energy and reactivity on the weak facets beneath wind slabs and new snow. See the profile below.

Column test in Beard Canyon today indicating reactive snowpack.

Additional precipitation warrants an assessment of wind loading in terms of aspect and elevation. Above treeline slopes are much more susceptible to wind slab formation.

Remember most slab avalanches occur during a storm or within 48 hours of accumulation.

The recent storm was not sufficient, however, to cover the many obstacles at lower elevations as the snowpack depth tapers to 15-20" below 10,000'.

Current Problems (noninclusive) more info

Wind slabs can form in extremely localized areas. Often only a few inches separates safe snow from dangerous snow. We often hear people say, “I was just walking along and suddenly the snow changed. It started cracking under my feet, and then the whole slope let loose.” - from avalanche.org

Wind slabs may also overload persistent weak layers in the upper snowpack. Extended column tests and collapsing snow have revealed this problem to exist below and above tree-line on northerly, northeasterly and northwesterly aspects.

Column test in Beard Canyon today indicating persistent slabs.

The bullseye slope angle for avalanche activity is 38 degrees. Moderating slope angles to 30 degrees and less drastically reduces the likelihood of triggering an avalanche.

Images

Note the reactive weak layer at 100 cm. Fracture propagation has increased in recent stability tests. This layer may become more sensitive with added snow, increasing avalanche potential.

Humphreys Peak on January 10th, 2019.

Final Thoughts

Backcountry permits are required for travel in the Kachina Peaks Wilderness and available at local USFS locations, as well as, at the Agassiz Lodge on Saturday and Sunday 8:30 -11:30 a.m.

For information on uphill travel within the Arizona Snowbowl ski area, please refer to www.flagstaffuphill.com and https://www.snowbowl.ski/the-mountain/uphill-access/ for details. Access to the Kachina Peaks Wilderness is available from the lower lots at Snowbowl via the Humphreys Trail and Kachina Trail.

Weather

Since then, gradual warming and average temperatures characterized the week. Wind has been light to moderate out of the south and southeast, until today when 30-50 mph north winds transported and sublimated much of the snow available for transport.

A short wave trough moves through this weekend with cloudy skies and snow flurries on Saturday and Sunday, January 12th and 13th. The following week will bring increasingly unsettled weather Monday through Wednesday with good chances of measurable precipitation, as a short wave passes over us on the leading edge of a more significant storm system.

At the time of publication, it was still too early to forecast the precise timing or impact of this major storm system, but it appears that at least the southern edge will hit us. The snow level is expected to be around 6,000 feet along the I-40 corridor and 7,000 feet to the south.

On Friday morning, January 11th, the Inner Basin SNOTEL site (Snowslide) reported a snow depth of 20 inches (51 cm) at 9,730 feet, and Arizona Snowbowl reported a settled base of 40 inches (102 cm) at 10,800 feet. So far this winter, 79 inches (201 cm) of snow have fallen at the mid-mountain study site. Since January 4th, SNOTEL temperatures have ranged between 19°F on January 8th, and 44°F on January 4th and 9th. For the same period, the AZ Snowbowl Top Patrol Station’s (ASBTP 11,555 feet) temperatures ranged between 12°F on January 6th, and 41°F on January 4th.

Authored/Edited By: David Lovejoy, Derik Spice, Troy Marino