Snowpack Summary for Friday, January 25, 2019 1:15 PM Wind dominated this week with significant snow transport and sublimation

This summary expired Jan. 27, 2019 1:15 PM

Flagstaff, Arizona - Backcountry of The San Francisco Peaks and Kachina Peaks Wilderness

Five inches of very light snow fell on January 20th at 10,800' with strong south wind. The wind trend this week started from the southwest and west, then shifted to the northwest and north, consistently 30-40 mph.

Much of our above treeline snowpack was moved to new locations or sublimated back to the atmosphere. Snow which loaded onto leeward slopes may have formed potentially dangerous wind slabs. Watch for pockets and pillows of wind loaded snow below ridgelines and sheltered sides of gullies. Wind slab avalanches could be triggered by the weight of a backcountry traveler.

Most recent wind loading is near ridgelines on southern aspects from this weeks persistent north wind. Whoompfing and collapsing was observed today, Friday morning.

No human triggered avalanches were reported with the mid January storm cycle. Observers found evidence of localized natural avalanche debris on lower North Core Ridge on January 23, though the event was likely from earlier in the week, possibly from the January 20th south wind event.

Below treeline may provide the best touring possibilities where slopes are protected from recent wind events.

Snowy weather last week has helped the lower elevation snow coverage. Currently 35"-50" (100-120 cm) of snow cover can be found between 9,000- 10,000' and more above. There are reports of good snow near 11,000' in terrain sheltered from wind affects.

Due to low elevation rain and warmth, the snowpack rapidly diminishes below 8,000', especially on sunny slopes.

Current Problems (noninclusive) more info

Failures have been reported on south and southeast slopes above treeline due to this weeks 30-40 mph north and northeast wind event.

Wind Slabs can be very hard, and may present a hollow drum like sound as you traverse the slope. If you are on an above treeline slope that is not wind scoured, then watch for thick hard wind slabs, and avoid.

The probability of a human triggering a persistent slab problem has decreased. However, a new wind slab plus a human trigger may be enough to collapse a persistent weak layer on some steep and isolated slopes.

Column test in Beard Canyon on January 11th indicating persistent slabs.

Images

Humphreys Cirque. Alternating wind events have produced wind slabs along ridgelines and various wind scouring affects.

January 23rd photo by Paul Dawson.

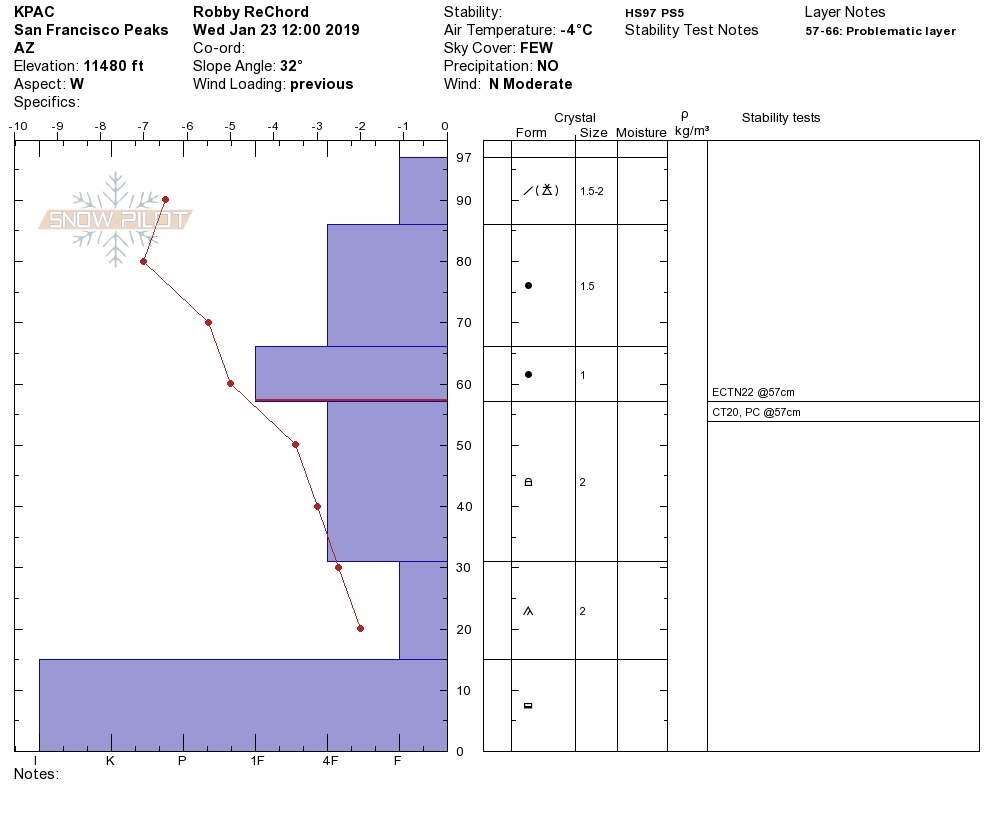

Snow profile from January 23, west aspect above treeline. Note the weak layer underneath wind slab at 57cm. Courtesy Robbie Rechord.

Final Thoughts

Backcountry permits are required for travel in the Kachina Peaks Wilderness and available at local USFS locations, as well as, at the Agassiz Lodge on Saturday and Sunday 8:30 -11:30 a.m. Permits are currently not being issued due to the partial government shutdown.

For information on uphill travel within the Arizona Snowbowl ski area, please refer to www.flagstaffuphill.com and https://www.snowbowl.ski/the-mountain/uphill-access/ for details. Access to the Kachina Peaks Wilderness is available from the lower lots at Snowbowl via the Humphreys Trail and Kachina Trail.

Weather

On Friday morning, January 25th, the Inner Basin SNOTEL site (Snowslide) reported a snow depth of 32 inches (81 cm) at 9,730 feet. Arizona Snowbowl reported a settled base of 51 inches (130 cm) at 10,800 feet. So far this winter, 128 inches (325 cm) of snow have fallen at the mid-mountain study site. Since January 18th, SNOTEL temperatures have ranged between 11°F on January 23rd, and 49°F on January 20th. For the same period, the AZ Snowbowl Top Patol Station (ASBTP 11,555 feet) temperatures ranged between 5°F on January 22nd, and 40°F on January 20th.

Authored/Edited By: David Lovejoy, Troy Marino, Derik Spice