Snowpack Summary for Friday, January 4, 2019 11:42 AM Coverage incrementally improving and more storms forecasted.

This summary expired Jan. 06, 2019 11:42 AM

Flagstaff, Arizona - Backcountry of The San Francisco Peaks and Kachina Peaks Wilderness

Natural avalanches are possible, and human triggered avalanches are probable on steep terrain, especially shaded and wind loaded aspects.

The recent cold spell has exacerbated temperature gradients in the snowpack: decreasing snowpack strength and increasing the creation of faceted, weak snow. Thus, the snowpack has poor structure, poor strength, and increasing energy = more potential for slab failure and propagation.

On January second whumphing and collapsing were reported on alpine northwesterly slopes. Snow pits reveal a weak faceted snow-layer below wind slabs. This persistent weak layer may get overloaded with new snow accumulations over the weekend. Up to a foot or more of snow is forecasted above treeline, and wind can easily transport this new snow and create sensitive wind slabs.

No avalanches have been observed nor reported this season.

For the next storm cycle, we recommend staying away from steep avalanche prone terrain until the snowpack has time to adjust. Should you go, cautious route finding, conservative decision making and snowpack evaluation will be essential.

Remember most slab avalanches occur during a storm or within 48 hours of accumulation.

Expect rocks and logs to be hidden under the light New Year's Eve snow.

Current Problems (noninclusive) more info

Wind slabs can form in extremely localized areas. Often only a few inches separates safe snow from dangerous snow. We often hear people say, “I was just walking along and suddenly the snow changed. It started cracking under my feet, and then the whole slope let loose.” - from avalanche.org

The snowpack is exhibiting increased energy during recent stability tests. Carefully evaluate slopes on all aspects and elevations.

The bullseye slope angle for avalanche activity is 38 degrees. Moderating slope angles to 30 degrees and less drastically reduces the likelihood of triggering an avalanche.

Images

Wind affected snow near top of Snowslide Canyon area.

January 2nd photo by Troy Marino

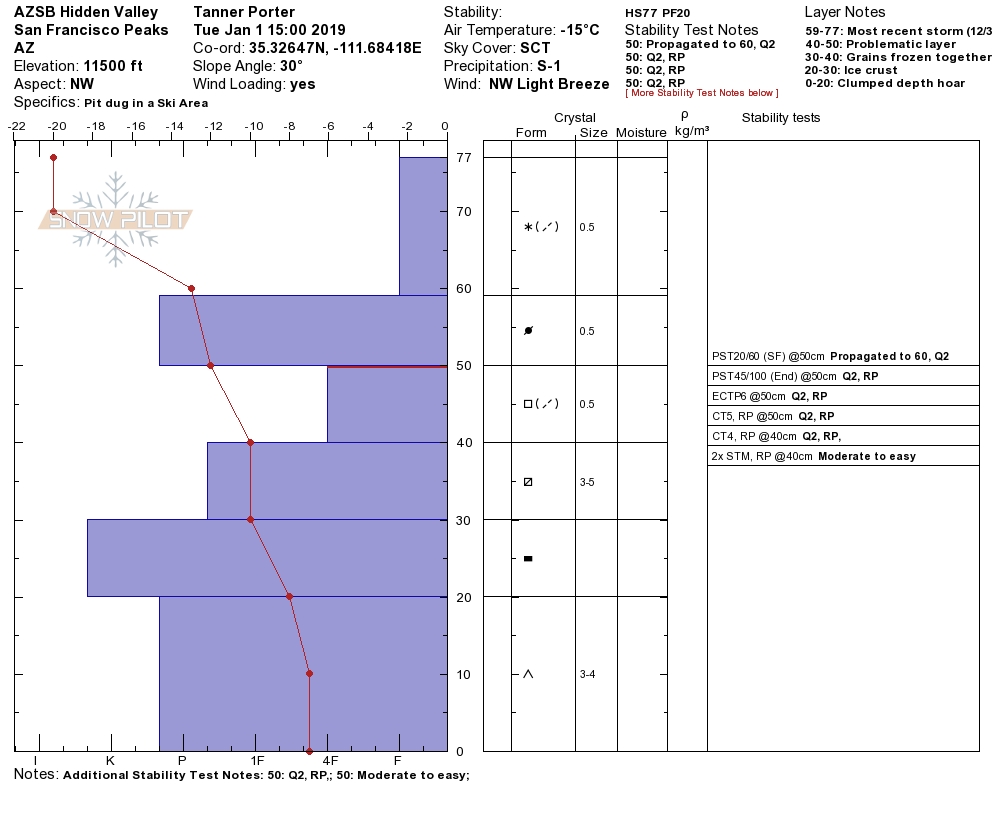

Snow profile from January 1, 2019. Near surface facets continue to be reactive underneath recent localized wind slabs at and above treeline.

Final Thoughts

Backcountry permits are required for travel in the Kachina Peaks Wilderness and available at local USFS locations, as well as, at the Agassiz Lodge on Saturday and Sunday 8:30 -11:30 a.m.

For information on uphill travel within the Arizona Snowbowl ski area, please refer to www.flagstaffuphill.com and https://www.snowbowl.ski/the-mountain/uphill-access/ for details. Access to the Kachina Peaks Wilderness is available from the lower lots at Snowbowl via the Humphreys Trail and Kachina Trail.

Weather

The work week ended with clear skies, and rising temperatures as a ridge of high pressure built. Fair weather will be short-lived, interrupted by the arrival of a cold front on Saturday. This one appears to be tapping into significant sub-tropical moisture, potentially adding to the storm’s productivity. This storm is expected to arrive late Saturday night and last into the beginning of next week. Eight to sixteen inches of higher density new snow is anticipated. The snowline will be 4,500-5,500 feet in northern Arizona. There is another storm on the distant horizon, probably impacting our region midweek. It is too early to predict the details at the time of publication, so stay tuned.

On the afternoon of January 3rd the Inner Basin SNOTEL site (Snowslide) reported a snow depth of 18 inches (46 cm) at 9,730 feet; and Arizona Snowbowl reported a settled base of 36 inches (91 cm) at 10,800 ft. So far this winter, 69 inches (175 cm) of snow have fallen at the mid-mountain study site.

Since December 29th, SNOTEL temperatures have ranged between -7°F on January 1st and 40°F on January 3rd. For the same period, the AZ Snowbowl Top Patrol Station (ASBTP— 11,555 feet) temperatures ranged between -4.5°F on January 1st and 40°F on January 3rd.

Favorable wind velocities to transport snow were recorded out of the north and northwest at the ASBTP Station between 4 pm on January 2nd and 7 am on January 3rd potentially loading south and southeast facing slopes.

Authored/Edited By: Troy Marino, David Lovejoy, Derik Spice