Snowpack Summary for Friday, December 13, 2019 2:00 PM Snowpack stabilizes with a weak layer underneath.

This summary expired Dec. 15, 2019 2:00 PM

Flagstaff, Arizona - Backcountry of The San Francisco Peaks and Kachina Peaks Wilderness

Since then, cool temperatures and dry conditions have allowed new snow to bond, stabilizing the upper snowpack. Winds have been light to moderate out of the southwest and west. No new avalanches have been reported since the late November cycle.

Wind exposed terrain has been stripped of new snow cover, resulting in icy “slide for life“ conditions. Crampons and ice axe or self-arrest ski poles may be necessary to prevent dangerous sliding falls.

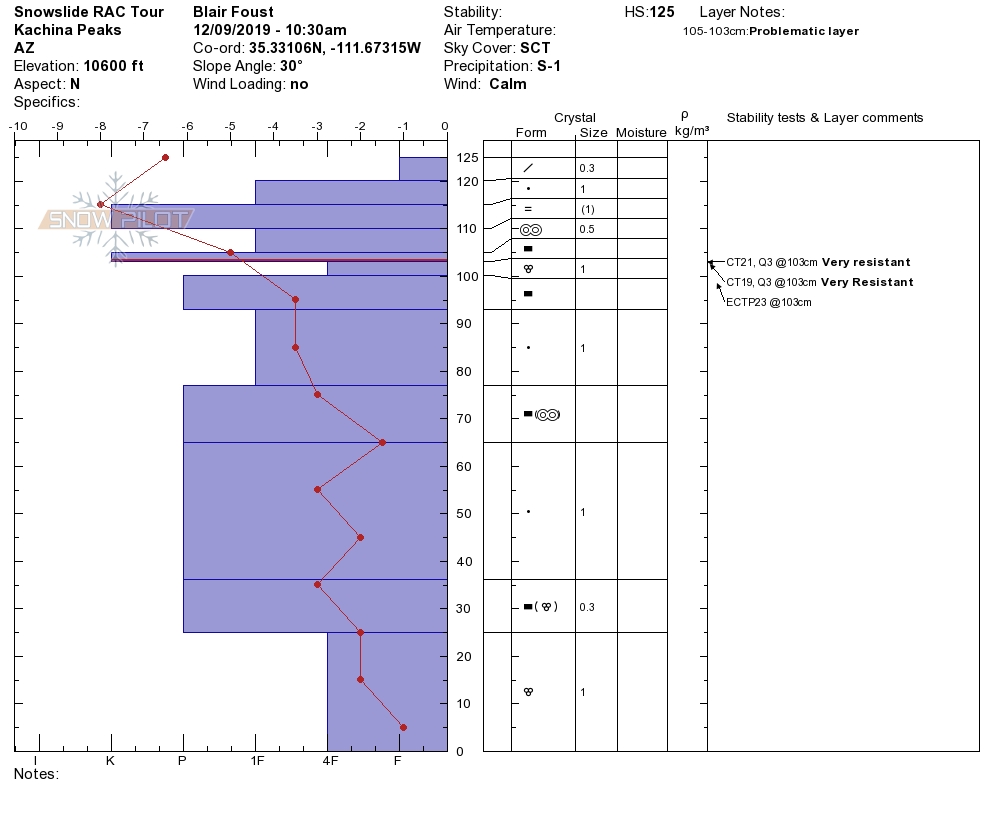

Worthy of note and of growing concern is the development of faceted near surface crystals observed by several observation teams. These are associated with the rain crust from the December 4-5 storm. Observers have noted this new weak layer of near surface facets (NSF), has demonstrated reactivity by propagating a fracture when using Extended Column Tests (ECT). Facets were noted on both top and bottom of this crust.

Until the next storm or wind event, the likelihood of natural avalanches seems low. However, human triggered avalanches where the new weak layer is found, may be possible. Do not let your guard down. Localized pockets of instability can linger after generalized conditions stabilize, especially on shaded aspects and colder elevations.

Wind slabs formed on top of near surface facets could be particularly reactive. Even a few hours of sustained winds of 15-40 mph can create dangerous wind slabs on leeward facing slopes and on cross loaded gullies at and above treeline. It is always prudent to avoid pillowed or hollow sounding slopes (>35 degrees) until stability tests indicate good bonding with the snow below the slab.

Snowpack stability could become threatened by a change in our current fair weather pattern. Colder unstable conditions are in the forecast, as current high pressure is replaced by a cold front. The forecast is for light snow. If current predicted snowfall is exceeded, an increase in avalanche hazard may be the result.

Coverage for ski touring is still good for this time of year, but early season hazards such as downed trees, stumps, and boulders may still remain hidden near the surface at lower elevations.

Current Problems (noninclusive) more info

Read more for hints on assessing persistent slab problems

Digging pits and using the Extended Column Test (ECT) or the Propagation Saw Test (PST) are your most reliable tools. Remember, if the test produces fracture propagation, no matter how strong the slab, the result is always a bad sign and should influence your critical assessment and decision making.

Images

Glazed crust on snow surface from the December 8-9 storm. Crampons and ice axe may be useful in preventing uncontrolled sliding falls. Photo by Tanner Porter

Pit profile illustrating weak layer developing below rain crust, creating potential persistent slab problem. Pit from Blair Foust

Final Thoughts

For information on uphill travel within the Arizona Snowbowl ski area, please refer to www.flagstaffuphill.com and https://www.snowbowl.ski/the-mountain/uphill-access/ for details.

Weather

Following mid-high elevation rain and a few inches of snow last weekend, conditions have been dry, cool and occasionally breezy. Mountain temperature were moderate (20- 30s deg F) having a generally stabilizing influence on the snowpack.

Looking forward, brisk winds out of the west and southwest (15-25 mph) will precede an approaching cold front. The storm will arrive on Saturday bringing cooler temperatures and wind, but not much snow. Accumulations are expected to be 1-2 inches.

The aftermath of this front will issue in cold weather through the middle of the upcoming week. High elevation temperatures will sink to the low teens and single digits. Some warming will follow, as high pressure briefly prevails, but another storm could materialize by next weekend. Overall, zonal flow seems to be establishing itself, with most of the mid-latitude cyclonic energy passing to our north.

Arizona Snowbowl Ski Patrol reports a 49” (124 cm) base at 10,800 ft. Snowslide SNOTEL reports a 32” (81cm) snow depth. So far this winter we have had 91” (231 cm) of snowfall at 10,800 feet.

Since December 6, SNOTEL temperatures have ranged between 12° F on December 9th and 44°F on December 12th. ASBTP station (11,555') reported a low of 14°F on December 9th and a high of 41°F on December 6th.

Authored/Edited By: Derik Spice, David Lovejoy