Snowpack Summary for Friday, February 8, 2019 10:00 PM February Roars in with a large avalanche in Snowslide Canyon

This summary expired Feb. 10, 2019 10:00 PM

Flagstaff, Arizona - Backcountry of The San Francisco Peaks and Kachina Peaks Wilderness

Natural avalanches are possible and human triggered avalanches are likely, primarily above 11,000 on northeast and easterly aspects. Northwest, north and possibly southeast aspects should be considered suspect.

Travel in avalanche terrain near and above treeline will be least reactive on west, southwest, south and southeast slopes, as long as the slopes are not connected to northwest and easterly slopes. Hopefully the right combination of wind/clouds/temperatures will keep the snow in good shape on these sunny slopes. But remember, improving stability does not mean that no avalanche hazards exist.

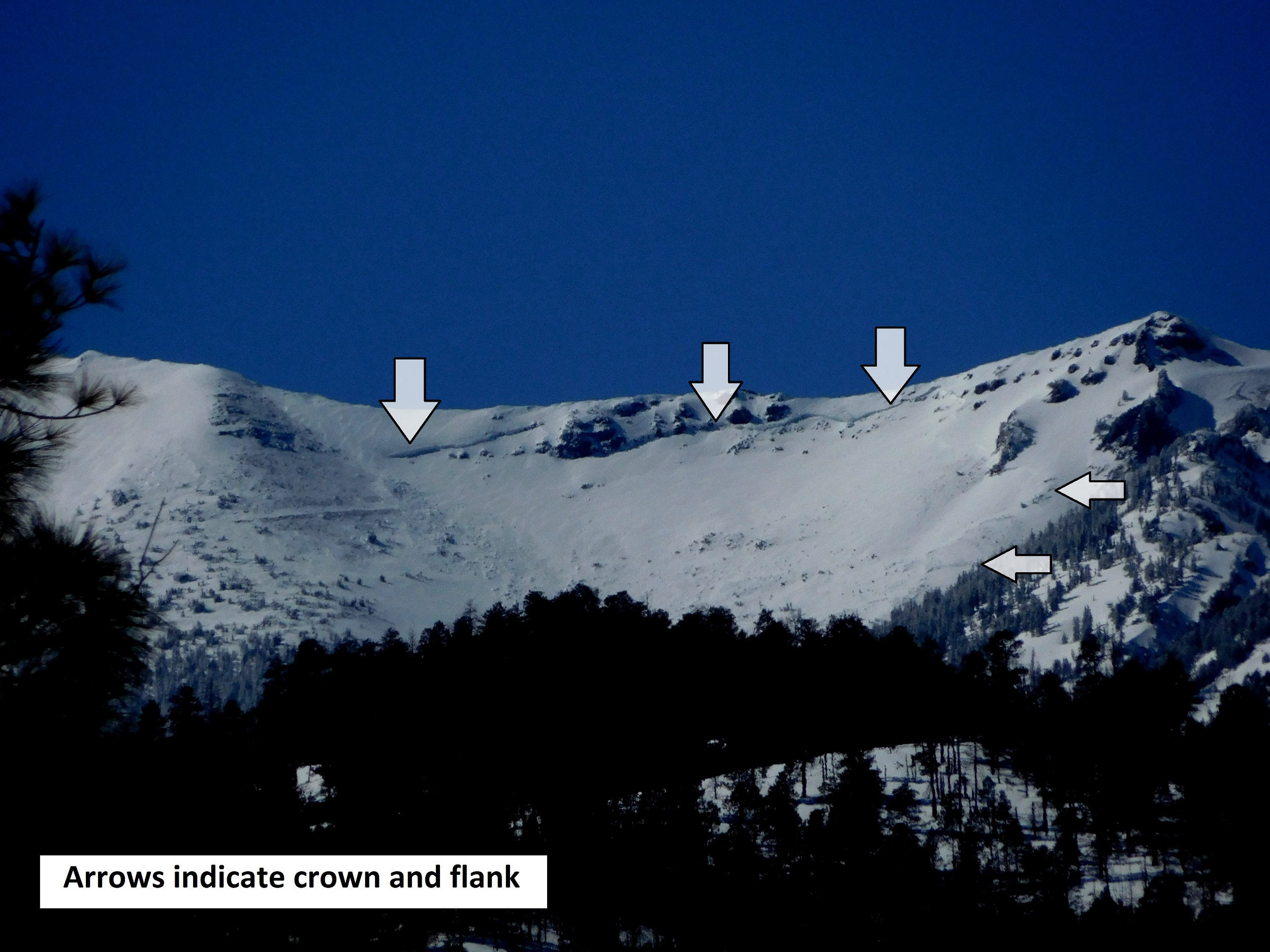

Snowslide Canyon Bowl avalanched (photo below). This likely occurred between February 5th, Tuesday night and February 6th, Wednesday morning. This is primarily an east aspect with some southeast and northeast. The crown was over 600m wide, and it ran over 1100m (0.7 miles). There is more crown not shown in the photo that wraps around Snowslide Canyon. The average crown height was 1m with a maximum of 1.75m. The avalanche failed on facets near the ground. The bed surface was old snow and crusts. Characteristic classification is HS N R4D4 O.The slope angle was between 35° and 42°.

Watch for reactive persistent weak layers. These may be buried under 2 to 5 feet of slab on east, northeast, north, and northwest aspects. Southeast aspects may be suspect as well, especially on slopes connected to easterly aspects.

Prior to this week's precipitation, wind scoured zones reduced the snowpack down to bedrocks in some areas. Also, sun and wind conspired to create hard snow prior to recent precipitation. Crampons may be helpful where new snow has been wind-scoured down to hard icy snow.

You will find great snow and low avalanche hazard if you stay off and do not get under slopes that are greater than 30°.

Current Problems (noninclusive) more info

Post weekend winds may create slabs on other aspects. As always watch for cross loading in gullies. Slopes just below ridges and on the flanks of shoulders should be considered suspect.

This problem has been found below, near and above treeline on northwest, north, northeast and east aspects. Our most reactive stability-test failures have occurred near and below treeline. The Snowslide Canyon avalanche crownline was above treeline.

Images

February 7th photo showing the Snowslide Canyon avalanche. Likely triggered on February 5th or 6th by storm/wind slab developing above a persistent slab problem.

Snowslide Canyon avalanche track. Photo from Feb. 8th.

Final Thoughts

Backcountry permits are required for travel in the Kachina Peaks Wilderness and available at local USFS locations, as well as, at the Agassiz Lodge on Saturday and Sunday 8:30 -11:30.

For information on uphill travel within the Arizona Snowbowl ski area, please refer to www.flagstaffuphill.com and https://www.snowbowl.ski/the-mountain/uphill-access/ for details. Access to the Kachina Peaks Wilderness is available from the lower lots at Snowbowl via the Humphreys Trail and Kachina Trail.

Weather

The past week has been the wettest so far this winter. Arizona snowbowl (10,800') reported 42" of new snow since Feb. 2nd. Twenty inches fell between Feb. 5th and 6th. The Snowslide SNOTEL (9,730') reported 22" since Feb. 2nd and 9" since the 5th. SNOTEL reported 4.8" of new snow water equivalent (SWE) between Feb. 2nd and 6th.

In the aftermath of this storm cycle, cold windy conditions have prevailed. Determining accurate ridge-top wind velocities and direction has been impossible since the ASBTP station's anemometer was incapacitated with rime ice. Lower elevation stations, such as the Flagstaff Pulliam Airport (elev. 6994') reported wind speeds between 15-30 mph, gusting to 30-40 mph, throughout the day on Wednesday February 6th.

Cool blustery days will continue into the weekend with wind chill temperatures as low as -17 F on Friday and a chance of snow showers on Saturday from a passing shortwave trough. Ridge-top wind speeds will continue in the teens and higher, gusting to 30-40 mph out of the southwest throughout the weekend. More unsettled weather and a chance of light precipitation is predicted to develop early in the workweek. A more promising chance for significant new snow will come later in the week. Models disagree on impact and timing, but this appear to be a wet storm with a snowline at or above 8000 feet, probably arriving on Thursday, Feb. 14th.

On Friday morning, Feb. 8th, the Inner Basin SNOTEL site (Snowslide) reported a snow depth of 50" (127 cm) at 9,730'. Arizona Snowbowl reported a settled base of 70" (178 cm) at 10,800'. So far this winter, 170" (432 cm) of snow have fallen at the mid-mountain study site. Since February 1st, SNOTEL temperatures have ranged between 5°F on February 7th, and 35° F on Feb. 2nd. For the same period, ASBTP (11,555') reported temperatures between -6°F on Feb, 7th, and 31°F on Feb. 1st and 2nd.

Authored/Edited By: David Lovejoy, Troy Marino, Derik Spice