Snowpack Summary for Friday, January 31, 2020 2:11 PM A Few Inches of Fresh and Mid-Season Snowpack Depth

This summary expired Feb. 02, 2020 2:11 PM

Flagstaff, Arizona - Backcountry of The San Francisco Peaks and Kachina Peaks Wilderness

Windblown, re-deposited snow has potentially created areas of unstable wind slab, most likely on south and southwest aspects near and above treeline, and cross-loaded along leeward sides of gullies and spurs. Until slabs stabilize, these could potentially result in small to medium sized avalanches that could be triggered by humans. Until significant additional precipitation or warm temperatures arrive, natural avalanches will be unlikely, but human triggered wind slab avalanches will be possible. At the time of publication, no new slab avalanches had been reported since the Christmas storm cycle.

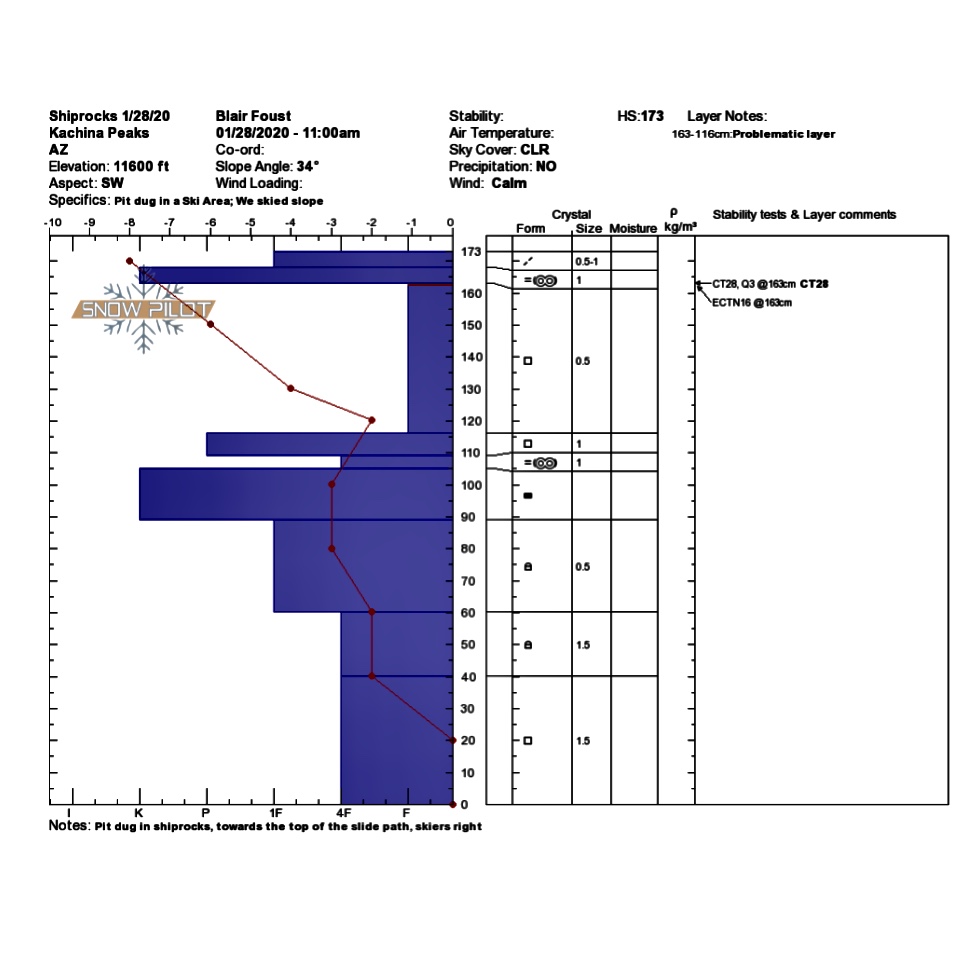

On the other hand, a recent snow pit from above treeline on a southwestern aspect showed evidence of near surface faceting. These new crystals are forming due to a temperature gradient recently created by cold air temperatures cooling the top 40 cm of an otherwise warm snowpack (see pit profile). So far these facets do not seem to be forming a reactive weak layer, but this development is something to keep an eye on, particularly if this layer gets covered by new snow.

Although the snowpack above treeline is still quite cold, warm periods between mini-storms are showing early signs of moving towards springtime conditions. The snowpack has become denser (stronger) and internal temperatures have become more uniform. The snowpack is progressing toward an "isothermal" state, one in which the entire snowpack is the same temperature (0° C). An isothermal snowpack is more predictable, because persistent weak layers are less apt to develop.

However, it should be noted that this progression could be temporary. It is not unusual for winter to return to northern Arizona after the apparent first signs of spring. Cold, dry snow conditions are frequently experienced in February and even into March.

New snow that fell over the past week has become redeposited as wind slab or vanished via sublimation. Caution is advised when approaching leeward terrain or cross-loaded deposits where wind slabs may have developed. Dangerous wind slab may soon bond to the snowpack underneath and stabilize after 24-48 hours.

Daytime warming will lead to deteriorating stability on sun exposed terrain. Be alert to conditions that change with elevation, aspect, and time of day. Adjust your travel plans accordingly. If snow underfoot becomes wet and slushy, move to cooler terrain.

Video below from Monday January 27, showing snow saltation in the foreground and turbulent suspension in the background.

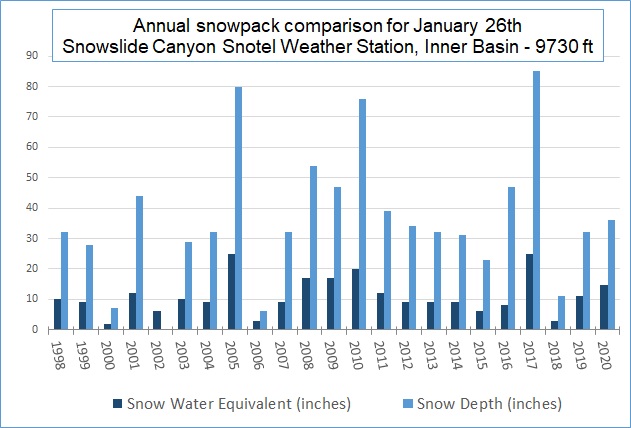

Every year on January 26th we update our annual snowpack comparison graph (posted below). This data is from the Snowslide Canyon Snotel located in the Inner Basin. For January 26th, 2020 the snow depth was 36" and the snow water equivalent (SWE) was 14.7". SWE is used to gauge the amount of liquid water contained within the snowpack. In other words, it is the depth of water that would result if the snowpack was instantly melted.

The 2020 snow depth of 36" is slightly below the 1998-2020 average of 38 inches, and the 2020 SWE of 14.7" is well above the average of 11 inches. From these numbers we can calculate the percent water density of the snow (SWE / depth x 100). For January 2020 the percent water density at the Inner Basin Snotel was 41 percent. For comparison, powder snow is generally <10 percent. This year's density is very high compared to other years. The highest measurement was on 2006 at 50 percent, but the snowpack was only reported as 6" deep on January 26, 2006, a low-snow year and probably saw a lot of melting. This year's high density snowpack is likely the result of several rain on snow events between November and January. Also, the dry spell and warmer temperatures over the last few weeks have settled and densified the snow.

Current Problems (noninclusive) more info

As corn skiing options start to open, timing is key to avoiding hazards associated with a warming snowpack. Keep away from steep, sun exposed terrain as stability deteriorates during the heat of the day. Warming may be accelerated near dark rock outcrops, where solar radiation is intensified by heat absorption. Snow roller or sloughs emanating from rock bands or outcrops are a sign of rising instability.

Images

Snow pit profile showing significant temperature gradient in the upper section of the snowpack. Pit by Blair Foust

Final Thoughts

Submit your observations here. You may save a life! The link to this form is now on our home page and snowpack menu.

For information on uphill travel within the Arizona Snowbowl ski area, please refer to www.flagstaffuphill.com and https://www.snowbowl.ski/the-mountain/uphill-access/ for details.

Weather

On Sunday night, a fast moving, short wave trough passed through freshening the snowpack with 6" of new snow at 10,800 feet. A similar storm on Wednesday January 29th failed to produce measurable snow. Post frontal winds out of the west, shifting clockwise to the north and northeast, moved much of the new snow onto southern and southwestern aspects, or sublimated moisture back into the clouds. Average wind speeds in the 20-40 mph range were recorded most of the day on Monday and Thursday in the wake of these low pressure systems.

Looking into the future, wind will persist and even strengthen on Friday, eventually yielding to a calm and pleasant weekend with building high pressure. Fair weather will be short-lived as a cold front dips into our region. It will bring low temperatures, high southwesterly winds, and a chance of snow early in the workweek. The greatest chances of significant precipitation seem to be on Monday night.

Arizona Snowbowl reported a 57” (145 cm) base at 10,800 feet. Snowslide SNOTEL reports a 36” (91 cm) snow depth. So far this winter, we have had 145” (368 cm) of snowfall at 10,800 feet.

Since January 24th, SNOTEL temperatures have ranged between 12° F on January 30th and 41° F on January 25 and 26th. ASBTP station (11,555 ft) reported a low of 9.6° F on January 30th, and a high of 38° F on January 25th.

Authored/Edited By: Troy Marino, David Lovejoy, Derik Spice