Snowpack Summary for Friday, March 20, 2020 3:52 PM Avalanche Hazard Increases with 32" Storm Total

This summary expired Mar. 22, 2020 3:52 PM

Flagstaff, Arizona - Backcountry of The San Francisco Peaks and Kachina Peaks Wilderness

Heavy snowfall was reported on Wednesday afternoon and night, tapering off on Thursday. Winds were moderate out of the southwest. 32 inches of new snow was reported at 10,800 feet by Friday morning. On March 19th, KPAC observers found dramatic signs of instability near the summit of Doyle Peak in the Inner Basin.

Another group on March 20th found propagation propensity at the top of telescope path—Failure of weak layers produced slopewide 'whoomphing', and stability tests proved reactive.

This significant load on a structurally fragile snowpack will increase the potential of dangerous avalanches. For at least the next 24 hours, natural slab avalanches will be possible and human triggered slab avalanches will be likely on steep terrain (30-45 degrees) near and above treeline.

To help prevent the spread of COVID-19, Arizona Snowbowl has suspended all operations until further notice. Snowbowl road is currently closed until further notice, and backcountry access points will require long approaches, e.g. Lockett Meadow road.

Be prepared and recognize the time and physical commitment of such an endeavor. With the ski area closed, the wilderness setting may pose additional challenges for rescue. Make conservative decisions and keep your risk acceptance low, for yourself and the community. Now is not the time to visit a hospital which may be overwhelmed due to COVID-19.

- 90% of human triggered avalanches happen during or within 24 hours of snowfall. Waiting 24 hours before traveling on, or, under steep (>30°) slopes will decrease your likelihood of triggering an avalanche.

- Venture into this new snow with an "assessment" mindset by selecting conservative terrain in which to gather information

- Check the bonding and reactivity of new storm and wind slabs.

- Look for signs of recent avalanches.

- Watch for instabilities like cracks shooting out from your skis or boards as you skin or ride in fresh snow.

- Listen for collapses (whomping) underfoot.

- Post storm sunny/warm weather may destabilize new slabs (spring equinox is March 19th).

- Make good decisions upon your observations.

- The extended forecast suggest even more unsettled weather next week, keep your guard elevated.

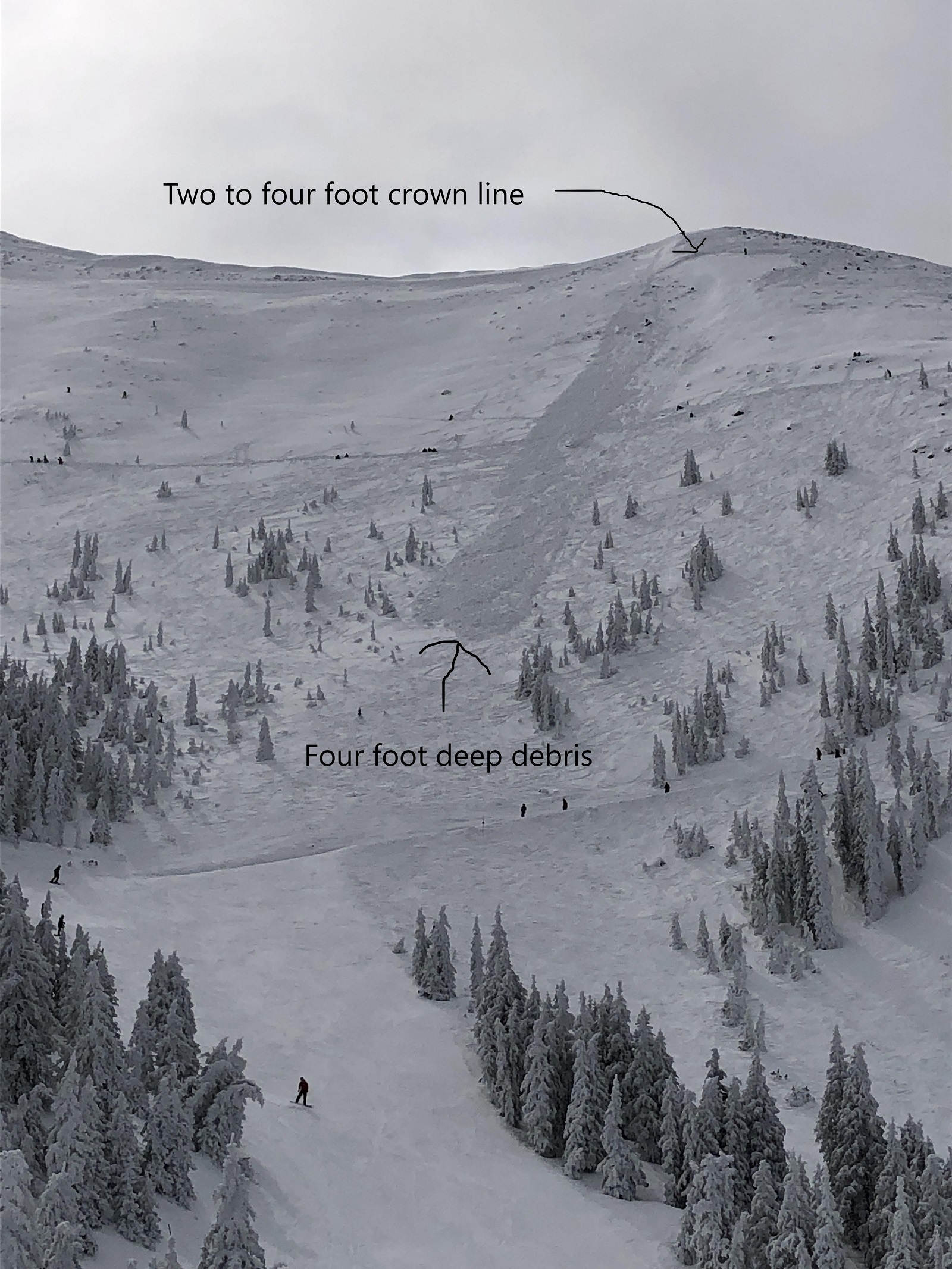

This was a wind slab that failed on needles resting on the March 11 rain crust. Recent pits reveal that this may have been an isolated snowpack structure, but KPAC encourages backcountry users to analyze the March 11th rain-crust (and above layers) on, or near treeline slopes, especially where you find wind loading.

Approach ridges and leeward terrain with caution. Wind can deposit snow 10 times more rapidly than snow falling from the sky multiplying the load on the snowpack. Be very suspicious of any steep slope with recent deposits of wind drifted snow.

Even though there is new snow, there may still be areas of exposed ice and hard snow. If you plan to to go above treeline, take an ice axe and crampons as a precaution. Some windward areas of the peaks were stripped of snow during the February high-wind events, while others have retained 3-6 feet of snow depth.

Current Problems (noninclusive) more info

Wind typically transports snow from the upwind side of terrain features and deposits snow on the downwind side. Wind slabs are often smooth and rounded and sometimes sound hollow, and can range from soft to hard. Wind slabs are usually confined to lee and cross-loaded terrain features. They can be avoided by sticking to sheltered or wind-scoured areas.

This crust is now buried 1.5-3 feet below the snow surface. Although we speculate that this condition is more isolated than widespread, reports from a variety of elevations identified this condition, generally on N and NW aspects. Tests results showed: CT12 Q1 and ECT P23, sliding on the 3/11 rain crust, 65cm down.

Images

March 14th avalanche triggered by explosives at AZ Snowbowl. Photo by Chad Trujillo.

Closer view of the crown line of 3/14 explosive triggered hard slab avalanche. Photo by Ken Galinski,.

Final Thoughts

Always carry the 10 essentials and avalanche rescue gear for wintertime wilderness travel. Submit your observations here. You may save a life!

Weather

A deep trough originating in the northern Pacific has brought 20- 30” of fresh snow to the Peaks, along with low temperatures, and low to moderate winds at treeline. The Arizona Snowbowl Top Patrol (ASTP) station (11,555’) has stopped transmitting as of Wednesday, limiting more recent data.

Forecast models predict a steady warming trend over the weekend and into the early workweek as the low-pressure system matures and dissipates. The recorded high temperature last week was 33°F on Tuesday. Nighttime temperatures dipped down into the mid-teens.

Next week brings the potential for more precipitation. On Monday, a short-wave trough brings a chance of precipitation, preceding a shallow northern born storm system on Tuesday through Thursday. As the week progresses, we will experience moderate to gusty winds and temperatures in the 20-30s degrees F at treeline. Precipitation potential is still uncertain, but March seems to be exiting with a bit of a roar.

Arizona Snowbowl reported a 85” ( 216cm) base at 10,800 feet. Snowslide SNOTEL reports a questionable depth of 61” (155cm) at 9,730 feet. So far this winter, 210" (533cm) of snowfall has been reported at 10,800 feet.

Since Friday March 13th, SNOTEL temperatures have ranged between 48°F on March 15th and 20°F on March 18th. ASBTP station (11,555 ft) reported a low of 16°F on March 16th and a high of 33°F on March 16th.

Authored/Edited By: David Lovejoy, Derik Spice