Snowpack Summary for Friday, February 3, 2017 6:34 PM Unseasonably warm temperatures are generally increasing snowpack stability.

This summary expired Feb. 05, 2017 6:34 PM

Flagstaff, Arizona - Backcountry of The San Francisco Peaks and Kachina Peaks Wilderness

No new natural or human triggered avalanches have been reported since Humphrey's Cirque and Snowslide Canyon avalanches, discussed in last week's snowpack summary.

The Snowslide Avalanche took out 10" diameter trees. This would have been an unsurvivable avalanche.

Unseasonably warm daytime temperatures have contributed to snowpack bonding, strengthening and densification. Snow from the storm cycle that produced 93" has settled and sublimated reducing its volume and mass by 10% or much more in some places. On some north aspects, much of the new snow was stripped by winds.

Across the San Francisco Peaks, widely variable windslab and stormslab layers sit atop decomposing facets and hard rain event crusts...Southwest facing upper elevation terrain may have a reactive wind slab from last Friday- Sunday's extended northeast wind loading event.

Watch for relatively shallow and recently deposited wind slab on northeast, east, and southeast facing aspects. As in the case with snow falling out of the sky during a storm, wind blown snow also needs time to bond with the snowpack below.

A delayed report was received from riders who triggered a loose snow, point-release avalanche on a steep north facing cinder cone slope, below 8000 ft. This very small avalanche occurred on January 25th.

Stability tests conducted in upper elevation starting zones show strong thick slabs with low to moderate reactivity on aspects besides the loaded southwest above treeline terrain. This wind slab is perched on top of a highly variable lower snowpack structure. Presumably the strong slab (four finger to one finger hardness) from the trifecta storm event occurring January 20th-23rd now have the strength to bridge old weak layers below. Propagation tests have revealed low fracture probation likelihood. The snowpack structure below the trifecta slabs is highly variable, ranging from preserved crusts and facets deep in the snowpack to homogeneous wind slab (top to bottom) and "sastrugi" (patterned snow cover where wind has eroded most of it). In areas where the snowpack is thick, the conundrum is, how strong is the slab? Although the likelihood of a skier or boarder triggering an avalanche seem low, the consequences if it were to slide might be very high, given the high volume and mass potentially entrained.

Coverage is still acceptable down to 7000 ft. but changing rapidly. The soft fun snow below 8000 ft may become melted and gone with the predicted warming trends.

Current Problems (noninclusive) more info

Images

Avalanche and crown flank fracture on easterly slopes of Snowslide Canyon. This occurred during the January 20-23, 2017 storm cycle, and later obscured by winds and snow.

Photo by Carlos Danel

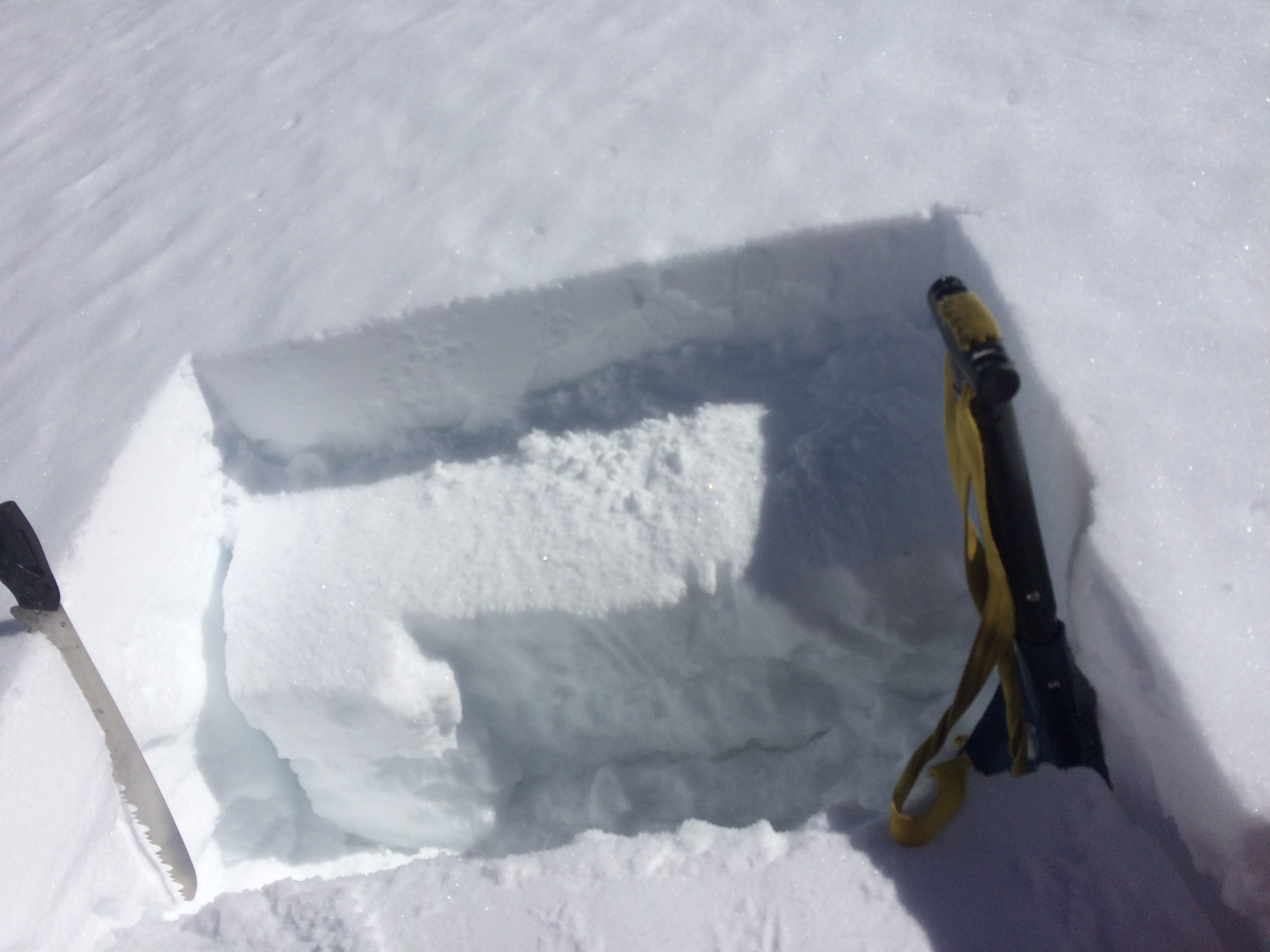

Hard slab failure on southwest slope at 11,400'. ECTP11Q1.

Final Thoughts

Travelers are advised to exercise caution, make slope specific evaluations and most of all, know where you are going and be prepared for the unexpected. As always, please treat this summary with appropriately guarded skepticism, make your own assessments, and contribute to our body of knowledge by reporting your observations.

Arizona Snowbowl uphill policy.

Want to learn more safe backcountry habits? KPAC offers level I and II avalanche courses. They are filling up fast!!!

During winter, backcountry permits are required to access the Kachina Peaks Wilderness. More info

Weather

Weather station information:

On the morning of Friday February 3rd the Inner Basin SNOTEL site (Snowslide) reported a snow depth of 76 inches (193 cm) at 9700’, and Arizona Snowbowl reported 86 inches ( 219 cm) at 10,800’. Since January 27th, SNOTEL temperatures ranged between -1° and 48° F, and Agassiz station between 12 and 42° F.

Authored/Edited By: Derik Spice, David Lovejoy, Troy Marino